Emergent literacy is where a child’s journey with language truly begins, opening the door to curiosity, imagination, and a lifelong love for reading. It provides the earliest foundation for learning, shaping how children explore sounds, symbols, and stories in meaningful ways. At its core, emergent literacy is about giving every child the chance to build confidence with language long before formal schooling begins.

This stage matters because it begins at birth and shapes how children learn to connect spoken words with print, develop vocabulary, and build early writing habits. Without strong emergent literacy skills, children may struggle later with reading comprehension and classroom learning.

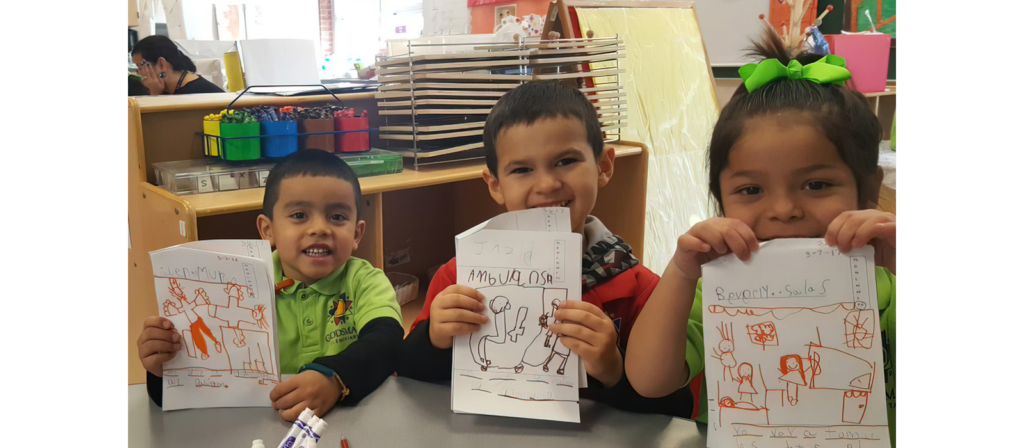

For instance, when a child sings along with rhymes, or scribbles on paper, they are already engaging in emergent literacy behaviors. These simple activities are the building blocks that prepare them for future success in reading and writing.

That is why understanding emergent literacy and supporting it through purposeful strategies is essential for both parents and educators. In the following section, we will define emergent literacy more clearly and explain its key features.

What Is Emergent Literacy?

Emergent literacy refers to the early reading and writing behaviors that begin at birth and lay the groundwork for conventional literacy. These behaviors are shaped by the child’s experiences, environment, and opportunities to interact with print and language.

The term emergent literacy was introduced by Teale and Sulzby (1986) to describe the range of reading and writing experiences that children engage in before they are formally taught to read and write.

More precisely, Koppenhaver and Erickson (2003) define emergent literacy as “all of the actions, understandings, and misunderstandings of learners engaged in experiences that involve print creation or use.” This broad but essential definition highlights the richness and unpredictability of early literacy development. It includes the moments when children mimic writing, pretend to read a story, or ask questions about logos and letters in the environment.

Key Characteristics and Behaviors

In practice, the emergent literacy stage is marked by observable behaviors such as:

- Scribbling with intention

- Pretending to read aloud

- Turning pages of a book correctly

- Asking what words mean

- Recognizing familiar signs or logos

These behaviors are not random. They represent the earliest signs that a child is building the emergent literacy skills needed for future reading and writing. Each small act reflects an understanding, or sometimes a misunderstanding, of how print and language function in the world.

Recognizing and supporting emergent literacy helps us build stronger readers before they ever begin decoding text. It allows educators and caregivers to nurture the underlying systems of literacy: oral language, symbolic understanding, and the motivation to communicate. In essence, emergent literacy is not only the first stage of reading; it’s the most formative one.

The Importance of Emergent Literacy

Academic Success

Children who develop emergent literacy skills early are far more prepared to succeed in school. These early experiences build the attention, comprehension, and communication abilities needed for classroom participation. When children enter kindergarten with a basic understanding of print, language, and storytelling, they adapt more easily to structured learning and show stronger academic performance in later grades.

Foundation for Reading and Writing

Emergent literacy forms the stepping stones toward conventional reading and writing. Long before a child can decode letters or construct sentences, they begin to build an understanding of how written language works. Recognizing that print carries meaning, experimenting with letter shapes, or retelling stories from pictures all contribute to the early development of core literacy skills. These early behaviors lay the groundwork for fluent reading and clear writing.

Vocabulary Acquisition

A major part of emergent literacy is vocabulary development. Children who are exposed to books, stories, and meaningful conversations from a young age tend to develop a broader vocabulary. This early word knowledge supports reading comprehension later on. The more words a child understands before entering school, the easier it is for them to make sense of what they read and to express themselves clearly.

Love for Reading

Perhaps the most powerful outcome of emergent literacy is that it helps foster a natural love for reading. When literacy is introduced through playful, engaging, and joyful experiences, children begin to associate books and language with pleasure, not pressure. This positive emotional connection motivates them to explore stories, ask questions, and seek out books on their own, turning them into lifelong readers.

How to Promote Emergent Literacy in the Classroom?

Promoting emergent literacy in early childhood classrooms requires more than just isolated lessons. It demands a language-rich environment, consistent modeling, interactive reading, and opportunities for playful exploration. These methods help build vocabulary, print awareness, phonological skills, and the motivation to read and write.

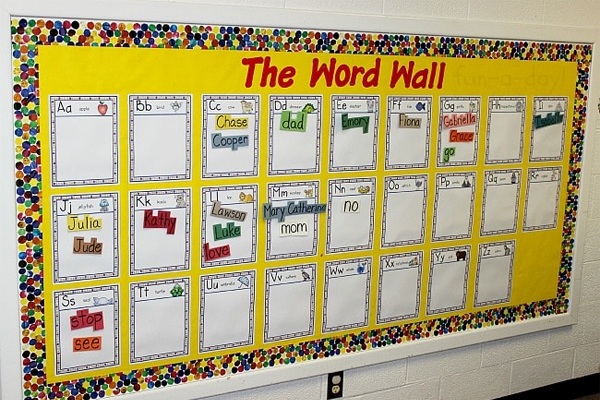

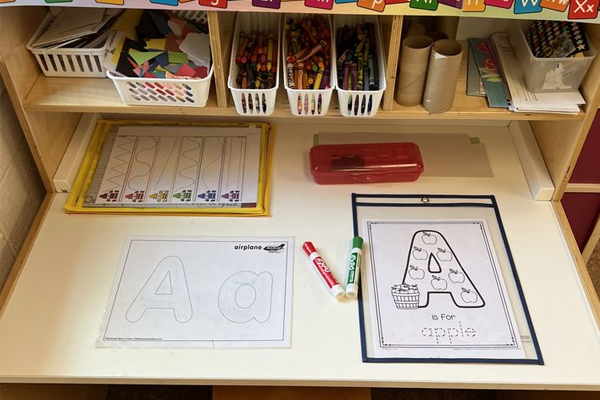

Create a Literacy-Rich Environment

A classroom that supports emergent literacy should immerse children in language and print at every turn. From a diverse, accessible classroom library to a dedicated writing center with pencils, markers, stencils, and paper, every corner should invite literacy. Label shelves, chairs, and objects with words to build print awareness. Display student work and hang posters with rhymes or classroom rules. Even interactive bulletin boards, like a “What I Learned Today” wall, can spark daily writing and storytelling.

Use Interactive Read-Alouds with Purpose

Read-alouds are one of the most effective strategies for building emergent literacy. Choose books that match the children’s interests and cultural backgrounds. Read expressively, using different voices and facial expressions to capture their attention. Ask open-ended questions that prompt prediction, empathy, and discussion. Use print referencing techniques to point out the title, author, direction of print, punctuation, and key vocabulary. When done right, read-alouds promote vocabulary growth, comprehension, and a love for reading.

Focus on Foundational Literacy Skills

Strong emergent literacy requires attention to foundational skills. Support phonological awareness with rhyming songs, clapping syllables, and sound-matching games. Build print awareness by teaching how to hold a book, turn pages, and recognize how print works. Develop oral language by encouraging children to talk, tell stories, role-play, and engage in rich conversations. These essential early literacy behaviors prepare children for decoding, writing, and reading with fluency later on.

Incorporate Play-Based Literacy Opportunities

Play gives children a natural way to explore language in context. Set up dramatic play areas like grocery stores or post offices with printed menus, signs, and writing materials. These spaces encourage children to read and write while role-playing. Add music and movement through songs, chants, fingerplays, and rhythm activities that reinforce phonemic awareness and syllables. Through meaningful, joyful play, emergent literacy skills develop in ways that feel effortless to children.

Promoting emergent literacy in the classroom isn’t about teaching letters in isolation. It’s about creating a space where children are surrounded by words, stories, and opportunities to use language with confidence. Through environmental design, read-alouds, foundational skills practice, meaningful play, and adult modeling, we give every child the tools to begin their journey as a successful, lifelong reader.

12 Emergent Literacy Activities for Preschoolers

The most effective emergent literacy activities for preschoolers are playful, purposeful, and grounded in everyday interactions. These activities help children develop skills such as print awareness, vocabulary, phonological awareness, and early writing through experience, not direct instruction.

Label Hunt in the Classroom

Give children simple “label finders” (e.g. cards with pictures or beginning letters) and ask them to walk around the room finding objects with printed labels: “door,” “sink,” “chair,” etc. Once they find them, have them match their card or point and say the word aloud.

Morning Message Routine

Start the day by writing a short message on the board: “Today is sunny. We will play outside.” Read it together, point to each word, and let a child circle a familiar letter or word. This builds left-to-right tracking and word recognition.

Syllable Clap Game

Say a word like “banana” and ask children to clap for each syllable: ba-na-na (3 claps). Use names, animals, and classroom objects to make it fun and personal.

Rhyme Sorting

Place picture cards on a table: “cat,” “hat,” “dog,” “log,” “sun,” “bun.” Let children sort cards into rhyming pairs. You can also sing rhyming songs and ask children to guess the final rhyming word.

“What’s in the Bag?”

Fill a mystery bag with real-life objects (e.g. toothbrush, apple, spoon). Children pull out one item at a time, describe it, and say what it’s used for. You can extend this by asking them to group items by theme (kitchen, bathroom, etc.).

Word of the Week Wall

Choose one new vocabulary word each week (e.g. “enormous”) and explore it through books, drawings, acting, and daily usage. Post it with visuals and encourage children to use it in sentences throughout the week.

Story Sequencing Cards

Provide cards with illustrations that tell a simple story in 3–4 steps (e.g. planting a flower). Children arrange them in order and retell the story using their own words. Add sentence starters like “First… Then… Next… Finally…”

Puppet Conversations

Use hand puppets to spark conversations or role-play. Let children use puppets to ask and answer questions, tell short stories, or act out parts from familiar books. This supports expressive language and narrative development.

Letter Tracing with Sensory Materials

Place sand, rice, or shaving cream on trays. Show a letter card and let children “write” the letter using their fingers. This builds muscle memory while engaging touch and sight.

Label the Picture

Give children a picture of a familiar object or scene. Ask them to draw something related and “write” a label for it. Encourage invented spelling or even single letters, as the goal is to help them understand that writing represents meaning.

Read and Act

Choose a simple picture book and pause to let children act out parts of the story. For example, in The Very Hungry Caterpillar, let them pretend to eat, grow, and turn into butterflies.

Sing and Write Rhymes

Sing familiar rhymes (like “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star”), then ask children to illustrate the rhyme or copy a repeated word or phrase. This reinforces rhythm, print awareness, and early writing together.

Effective emergent literacy activities don’t require expensive tools; they rely on intentional design, repetition, and joy. From clapping syllables to labeling classroom objects, each of these hands-on experiences helps preschoolers connect meaning, print, and language. These activities give every child the chance to build real literacy skills in ways that are playful, practical, and developmentally appropriate.

What is the role of parents in emergent literacy?

Preschoolers who are read to at home, spoken with regularly, and encouraged to engage with print develop stronger language skills, greater interest in reading, and higher readiness for formal schooling. In fact, early reading experiences with parents are often the most important predictor of a child’s language development and emergent literacy success, more impactful than socioeconomic status, family size, or even the parents’ own education levels.

What’s especially notable is that the effects of parental support last. While the early years are the most sensitive period for brain and language development, the influence of parental involvement continues well into adolescence and even adulthood. Studies show that a parent’s interest in their child’s learning journey is a reliable predictor of long-term academic achievement, even more so than income or access to tutoring.

That’s why it’s vital to equip parents with both the awareness and the tools to create literacy-rich environments at home. These environments don’t need to be elaborate. Labeling items around the house, setting aside 10 minutes each night for a bedtime story, or helping a child write a shopping list are simple yet powerful actions. When parents promote the idea that reading is fun and valuable, their children often become more motivated to read for pleasure on their own.

Difference Between Early Literacy and Emergent Literacy

Emergent literacy and early literacy represent two important but distinct phases in a child’s literacy journey. Understanding their differences helps educators and parents apply the right support at the right stage.

Before children learn to read and write in the traditional sense, they go through the emergent literacy stage. This phase begins at birth and includes all the experiences, behaviors, and understandings children gather through talking, playing, observing, and pretending. It’s informal, natural, and often playful.

Early literacy begins when children start to acquire specific, structured skills like letter recognition, sound blending, and early word decoding. This stage typically occurs closer to school age and includes more teacher-led instruction and practice.

While the two phases are connected, they focus on different aspects of development. Emergent literacy is about building awareness; early literacy is about applying skills. Both are essential for long-term reading success.

Key Differences Between Emergent Literacy and Early Literacy

| Kipengele | Emergent Literacy | Early Literacy |

|---|---|---|

| Muda | Begins at birth through the preschool years | Begins around kindergarten or when formal instruction starts |

| Mtindo wa Kujifunza | Informal, experience-based, embedded in daily play and conversation | Structured, skill-based, supported by intentional teaching |

| Main Focus | Awareness of print, oral language, curiosity, motivation | Letter-sound knowledge, decoding, phonics, handwriting |

| Child Behaviors | Scribbling, pretend reading, recognizing logos, talking about stories | Reading simple words, writing letters, matching sounds to symbols |

| Adult Role | Model language and reading; read aloud; create print-rich environments | Directly teach letter-sound relationships, reading strategies, writing formation |

| Mazingira | Playful and exploratory activities include books, songs, puppets, dramatic play, and labeled items. | More structured activities include phonics games, handwriting activities, and guided reading books. |

| Goal | Develop language confidence and understanding that print has meaning | Build the ability to read, write, and comprehend written text |

Emergent literacy lays the groundwork through natural exposure and playful exploration. Early literacy builds on that foundation with focused skill instruction. One stage prepares the mind; the other trains the method. Both are crucial, but each requires a different approach in both classroom and home environments.

Recommendations for the Most Useful Books on Emergent Literacy

The right books are essential tools for building emergent literacy. Stories with rhythm, repetition, predictable structure, and engaging visuals help preschoolers build vocabulary, print awareness, and oral language skills. Below are some of the most effective titles used by early childhood educators and parents worldwide.

Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? by Bill Martin Jr. & Eric Carle

Recommended Age: 2–5 years

This classic is perfect for daily read-alouds. Its repeating sentence structure, predictable pattern, and colorful illustrations help children anticipate language and join in as “readers.” It supports vocabulary development, rhythm, and early sentence structure.

Chicka Chicka Boom Boom by Bill Martin Jr. & John Archambault

Recommended Age: 3–6 years

With its bold visuals and musical rhythm, this book makes learning the alphabet fun and memorable. Children are naturally drawn to its rhymes and alliteration. It’s a go-to choice for teaching letter names, phonemic awareness, and sound-play.

We’re Going on a Bear Hunt by Michael Rosen

Recommended Age: 3–6 years

This story combines physical movement with language. Children love acting out the journey, repeating phrases, and retelling the sequence. It’s great for group participation and strengthens sequencing, oral storytelling, and narrative thinking.

The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle

Recommended Age: 2–5 years

This multi-layered book teaches days of the week, counting, healthy habits, and life cycles, all while building print awareness. Children engage with the visuals and love the repetition. It is ideal for thematic units and cross-curricular learning.

Dear Zoo by Rod Campbell

Recommended Age: 2–4 years

Perfect for interactive reading, especially with toddlers. Children enjoy lifting flaps, naming animals, and predicting what comes next. This book strengthens descriptive vocabulary, print motivation, and the concept of sequencing.

Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus! by Mo Willems

Recommended Age: 4–6 years

A favorite for developing expressive language and emotional literacy. The conversational style encourages children to respond to the character, making it perfect for dialogic reading and dramatic play. Supports oral language and reading comprehension.

Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown

Recommended Age: 2–5 years

This gentle bedtime story builds book handling skills, print awareness, and observation. Its repetitive structure makes it ideal for helping children predict words and recognize visual patterns in text.

The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats

Recommended Age: 3–6 years

A relatable, simple story that builds vocabulary and supports early narrative skills. It encourages children to talk about seasons, emotions, and personal experiences, making it great for story extension activities like drawing or class discussions.

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie by Laura Numeroff

Recommended Age: 3–6 years

This circular story structure teaches cause-and-effect thinking in a humorous, engaging way. It helps build comprehension, memory recall, and sequencing, all key aspects of emergent literacy.

Each Peach Pear Plum by Janet & Allan Ahlberg

Recommended Age: 3–6 years

A beautifully illustrated rhyming book that encourages children to look closely at pictures while predicting what comes next. It’s excellent for building rhyme awareness, vocabulary, and visual literacy.

Books are powerful teaching tools in early childhood education. These titles aren’t just entertaining, they are developmentally designed to support emergent literacy. Whether you’re reading aloud in a classroom or sending home a parent reading list, these books help children connect words, sounds, and meaning from an early age.

How Furniture and Environments Support Emerging Literacy Skills

A well-designed learning environment, supported by purpose-built furniture, plays a critical role in fostering emergent literacy skills. From how books are displayed to how writing materials are accessed, the classroom setup can either invite children into the world of literacy or push it out of reach.

Children learn to read and write long before they sit at a desk with a pencil. In fact, much of their literacy development begins by simply moving through a space that encourages them to engage with language naturally. When shelves are too high, books are hidden away, or materials are inaccessible, children miss out on countless opportunities for spontaneous learning.

Low, open bookshelves placed at children’s eye level make books visible, reachable, and inviting. When children can choose books independently, they develop print motivation, a key emergent literacy skill. Book displays with front-facing covers also help them connect visuals with titles and spark curiosity.

Clearly labeled furniture and materials help build print awareness. Labels on drawers, chairs, storage bins, and even bathroom doors turn every object into a reading opportunity. Children begin to understand that print has meaning and function in daily life.

Writing centers, when thoughtfully designed, offer a space for experimentation. Stocked with pencils, crayons, letter stencils, notepads, and name cards, these areas invite children to scribble, draw, copy letters, or write stories during free play. When children see writing as part of play, not just a task, they are more likely to engage with it meaningfully.

Flexible seating and reading corners support quiet literacy moments. Soft rugs, child-sized armchairs, or floor cushions help create cozy nooks where children can flip through books, read to a friend, or listen to a story. Comfort matters. When children feel at ease, they stay engaged longer and absorb more language.

In Reggio and Montessori classrooms, the environment is often referred to as “the third teacher.” That’s because every piece of furniture, every object, and every layout decision either supports or hinders a child’s natural drive to explore language. At Kidz mshindi, we design furniture that invites interaction, independence, and exploration—because that’s how real literacy begins.

How to Support Emerging Literacy Skills in Children with Disabilities

Every child, regardless of ability, has the right to develop literacy. With the right strategies, tools, and environment, children with disabilities can engage meaningfully with emergent literacy and build the same foundational skills as their peers.

First, access is everything. This means providing adapted materials like board books with sturdy pages, tactile alphabet cards, switch-activated audio books, or communication boards with visual symbols. These tools allow children to explore print and language even if traditional methods are inaccessible.

Next, educators must be intentional about offering repeated exposure. Children with disabilities may require more time and practice with the same text, activity, or sound. Repetition is not boring, it is necessary for learning. Reading the same book multiple times, pointing to the same word daily, or singing the same song can significantly reinforce memory and understanding.

Multisensory experiences are especially powerful. Pairing spoken words with visuals, physical objects, songs, or hand signs gives children multiple entry points into language. For example, using a plush apple while reading about fruit allows a child to touch, hear, and see the word “apple” in action.

Teacher and caregiver attitudes matter too. Children with disabilities thrive in environments where adults believe in their ability to learn, communicate, and grow. Celebrate every attempt at writing, every turn of a book page, and every effort to engage with a story, because for many children, these are major achievements.

Hitimisho

Emergent literacy is the foundation of every child’s language journey, guiding the development of vocabulary, print awareness, oral expression, and early writing skills. When families and educators nurture this stage with meaningful conversations, engaging books, and playful activities, children grow into confident learners ready for formal literacy. The environment also matters greatly, and classrooms that provide accessible books, writing tools, and well-designed furniture give children daily opportunities to practice and strengthen these essential skills.